Speaking at the Energy Transition World Forum at the Flame Virtual Event, Dieter Helm (Fellow, New College Oxford) discussed a roadmap to achieve net zero.

As part of his presentation, Dieter would cover the evolution of the European Energy policy and climate policy, and discuss the centrality of carbon pricing, carbon border adjustments, net zero infrastructures and offsetting.

In this article we explore four of the main themes from his presentation. We look at the real meaning of net zero, what has happened in the 30 years since the Kyoto Protocol, three economic principles for climate change, and the value of proper carbon pricing.

What Does Net Zero Actually Mean?

While it may seem obvious, it is not quite as simple as getting net emissions to zero. Helm believes that the United Kingdom and Europe’s view is derived from 1997 Kyoto Protocol, and even before.

“This is the idea that each country should adopt a unilateral carbon production territorial target. And the logic goes that if everybody did this then we would get to net zero, but not everyone is and not everyone will unless we get a global agreement - the chances of that happening are very, very slim,” asserts Helm. In all reality, this is not going to happen anytime soon.

“If you take a unilateral carbon production territorial approach,” observes Helm, “you should not kid yourself that when you get to net zero that you will no longer be contributing to climate change. It’s just wrong.” Helm continues, “It’s wrong because we’re never going to get to zero – nor should we – as net is very different from gross.”

Helm believes that in examining the real causes climate change, production is part of the equation but that the production is based on our behaviours of consumption. He adds, “that’s what oil, gas and coal companies do. That’s what steel companies do. It’s what chemical companies do and that’s what car companies do. They make it for us.”

In reality, if we were to ask what net zero carbon consumption look like, we are going to get a very different picture. Closing steel, car, petrochemical, and aerospace plants, would certainly be one of the best ways to achieving a net zero territorial carbon production target however, this would be a large increase in the amount of imports. While this would reduce territorial carbon emissions for a country, and they would get a tick in the box for being good at achieving their climate change targets, it would make climate change worse.

Helm believes that if you want to unilaterally make sure that when you get to net zero and no longer be causing climate change then the answer is that you have to get to net zero carbon consumption - which is a radically different ask from territorial production.

“What you realise is that it’s not about whether this stuff is made in the UK or Germany, it’s about wherever it’s made. It’s about the carbon content, and that’s because carbon is not territorial. It doesn’t matter where it is produced and that’s what really matters when thinking about climate change going forward,” states Helm.

Ultimately, identifying and stimulating low-impact, complementary consumption and trade components will be key to not only reducing carbon production, but reducing carbon consumption.

Kyoto To Cop26: 30 Wasted Years

In Helm’s view, goalsetting on the reduction of carbon production the reason why very little progress has been made in what he describes as the “wasted 30 years” since the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. He argues the phenomenal growth of China “for at least the first two and a half decades was based on energy and carbon intensive industry exports – steel, fertilisers, cement, petrochemicals, and aluminium.” When combined with the meteoric expansion on global trade shipping around the world, one starts to understand the magnitude of Helm’s argument.

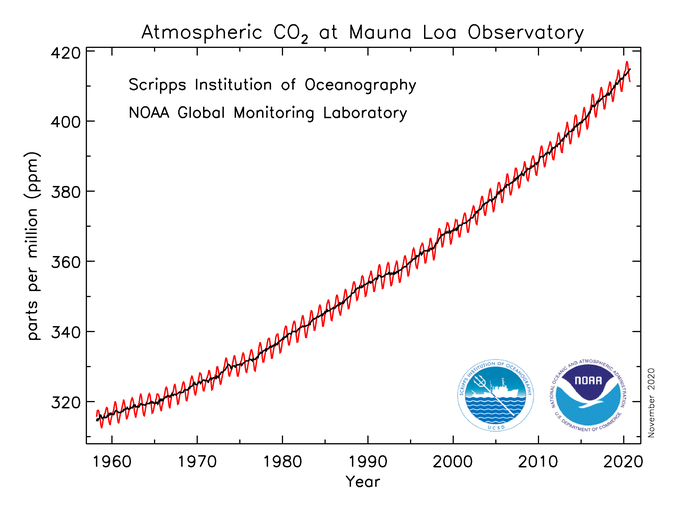

The truth is that over the last 30 years we have managed to add two parts per million carbon to the atmosphere every single year – and in some years more. “Even the coronavirus and the lockdowns have not broken that trend,” reflects Helm.

A chart showing the steadily increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (in parts per million) observed at NOAA's Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii over the course of 60 years. Measurements of the greenhouse gas began in 1959. Credit: NOAA/ NASA

Europe, and to a lesser extent the United States, has essentially been decarbonising the production but keeping the same trajectory due to consumption observes Helm’s. He notes that is “why 1990 was such a seductive year. The collapse of the Soviet Union gave us a very easy baseline to work from but look what happened subsequently… we will keep on going to our net zero carbon consumption, but will we achieve very much? No.”

Helm believes that this is the issue with The Paris Agreement. Even if the agreements were legally binding, the offers or intentions of various countries don’t add up to 2 degrees and refer to carbon production, not carbon consumption. He adds that it is a complete illusion to believe that any US president would ever sign a legally binding treaty and get that through the Senate. Similarly, Helm states, “What about the Chinese autocrat? China is now building more coal power stations now than the whole installed capacity of Europe.” He continues, “And if we look at Russia, look at the Siberian fires and the damage. Is there any evidence that Mr. Putin cares about climate change?”

In short, the real numbers don’t lie, and we cannot be selective about the reality of the situation. Our current goals are not fit for purpose and we need to come to inconvenient truth that the current way forward is going to achieve the objective.

3 Economic Principles For Climate Change

Helm acknowledges that we should keep reminding people of the issues, to keep telling them about the science and attend demonstrations however, “this is not actually going to crack our problem.” He continues, “we have to ask a serious question. What is it that we do really need to do if we actually want to do something about climate change?”

In Helm’s opinion, we begin by applying three, simple yet broad, economic principles – specifically around the allocation of scarce resources.

“Firstly, the polluter pays. If you don’t pay for the pollution you cause, you will not take it seriously,” asserts Helm. He adds that economically efficient markets internalise externalities, and that carbon would be priced in an truly efficient economy.

Helm states the public goods principle would apply too. The infrastructure would be built to decarbonise economies as he believes the market will not build these on its own.

Finally, a net gain principle would apply too. Helm explains that if “you cause pollution, or you cause net emissions, then you must compensate with sequestration.”

The Real Value Of A Carbon Price

There is an important distinction to be made about the carbon price which Helm refers too. He does not mean the mean the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) price which he believes is “short-term” and “volatile”, but rather a price which one can credibly investigate in the medium and long-term and see rising through time. Also, a carbon price which can be applied to transport, agriculture, and domestic heating, as well as electricity.

“Decarbonising electricity is not rocket science and we at least know how to do it, but transport emissions have gone nowhere since 1990, and the great delivery boom which has come from the internet and the coronavirus will make that worse,” declares Helm. He states that in agriculture, soils have four times the carbon of the atmosphere and yet we don’t measure properly the carbon being stripped out the soils by the common agricultural policy and sheer inefficiency of modern agriculture. “We need to price the carbon so that farmers have to pay for the pollution rather than be subsidised by cheap diesel and effectively use more carbon intensive chemical means of production,” he adds.

Helm says that generalising the carbon price is crucial, but this carbon price cannot just be a domestic price. It’s no good taxing carbon or having the EU ETS in Europe and then simply disadvantaging energy intensive producers in Europe. The obvious repercussions on this would be that energy producers close however; the reality is they do all their investing elsewhere.

Perhaps the answer to this lay in a carbon border adjustment? Yes, its might be difficult to calculate but Helm believes it is better to be “roughly right”, rather than “really precisely wrong.”

Helm contends that by working out what carbon pricing to apply domestically to goods and services these can applied to imported goods and services too. He adds that it doesn’t have to start with everything as “there are only about 5 big industries which account for most of the carbon global trade.” By starting with these there is still a mountain to climb, but the journey becomes far more manageable, and with greater impact from the start.

Interestingly, the carbon border adjustment (or price) creates a very different reality to current processes. “If a ton of steel, embedding loads of carbon, arriving in a country has to pay the same carbon price as a local steel producer, you raise a lot of money. As money is the route to getting a lot of internationalisation of the unilateral efforts so far to address climate change,” proclaims Helm.

Paying a foreign government carbon duty on the border is not favourable by any means hence a carbon tax at the country of origin is far more favourable. Organisations and local governments would prefer to have the revenue paid to their own government rather than a foreign one.

Helm suggests this leads to the idea that any country engaged in trade has a clear incentive in the border adjustment process to introduce their own carbon price. Helm adds that this bottom-up, carbon pricing route is vastly more potentially beneficial in climate change terms, and why we need to get serious about carbon pricing as part of the carbon plan.

In summary, Helm notes that carbon plan needs carbon pricing, it needs carbon boarder adjustments, it needs investment in the required infrastructures, and it requires proper offsetting. “And that’s the point of the plan, it’s a balance,” says Helm. “Climate change is not just about emissions, that’s one’s side of the seesaw, which is going badly up. The other side of the seesaw which is going down is the ability of the natural world to absorb that carbon,” he cautions.

In closing, Helm argues that the climate change crisis is “perfectly solvable” and does not require a revolution. “It’s about sensible, sane economic principals and I try to argue in this presentation. At the heart of those principles is the idea that we must make polluters pay – that’s you, and me,” he concludes.

The Energy Transition World Forum was a part of the Flame Virtual Event hosted online this year. Find out more about the 2021 events on the above links.